The extraordinary pace of progress is best seen in generative models, such as DALL-E-II, Stable Diffusion, MidJourney, and ChatGPT, producing images, text and speech that are near-indistinguishable from the work of humans. For what can only be described as a monumental leap forward in AI research, awe sits equally beside trepidation, as the prospect of more advanced and widespread AI systems raises sobering concerns. This has prompted an important shift in the public discourse around the consequences of ubiquitous AI in its current form, as well as the interplay between ideas around AI risk and value alignment.

In this article, we’ll explore the history of these ideas, why people think they are important, and how they play into our thinking here at harrison.ai.

In March 2023, the Future of Life Institute published an open letter, calling for a moratorium on the training of large language models (LLMs), the technology underpinning applications such as ChatGPT, Bing Chat, and Bard. The letter garnered the signatures of more than 25,000 supporters, among whom are famous AI researchers, scientists and public intellectuals such as Max Tegmark, Yoshua Bengio, Yuval Noah Harari and Stuart Russel.

This show of solidarity followed several months of ground-breaking discoveries of what this new class of models can do. Never have we seen AI so compellingly generate original jokes, explain complex topics in science and mathematics, write and debug code, generate Q&A exchanges and translate between multiple languages. Most profoundly, ChatGPT displays emergent properties which weren’t explicitly part of its training repertoire. In their ability to seemingly create novelty, we face the undeniable risk that such systems are inherently unpredictable. If we try to imagine what would be capable with even larger models trained on even more data, the uncertainties of intended and unintended consequences grow rapidly.

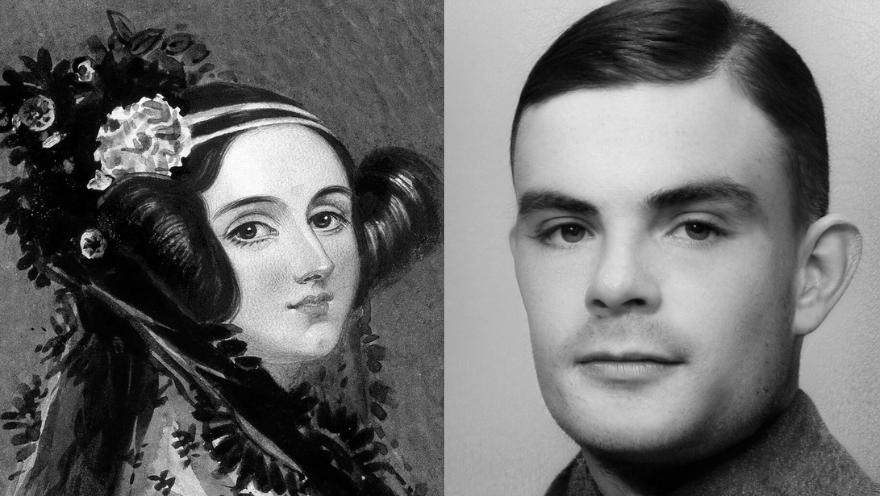

In 1843, Ada Lovelace was one of the first people to understand the transformation that computers would have on society, guessing that one day they “might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent” (see OpenAI JukeBox). However, she was sceptical that it could “originate anything [on its own, doing] whatever we know how to order it to perform”. In other words, humans would remain at the centre of knowledge creation, as she believed computers would only be able to do what humans programmed them to do. In 1950, Alan Turing referred to this as “Lady Lovelace’s Objection”, countering it with the idea that if put in control of its own design, and operation, “…at some stage, therefore, we should have to expect the machines to take control”. Recursive self-improvement would naturally lead to an “intelligence explosion”, as described by Irving John Good, a state where intelligent machines design new generations of machines which are more intelligent than what humans could design – which would see machines far exceed our (human) ability to keep pace. Such a vision has fuelled the curiosity and nightmares of people ever since.

It is true that the promise of AI is equally matched by its peril, the possibilities of both should be taken seriously. Yet, whatever path we choose, ever-present will be new problems across all scales. Small problems, severe problems, dangers, all the way up to existential dangers. The constant stream of old and new problems is only resolved via our constant stream of knowledge creation. Ultimately, it is the pursuit of knowledge that will determine whether we thrive in the face of problems of all kinds. AI offers humanity the chance to solve many age-old problems, and will help us solve the many more problems not yet known to us. Not pursuing AI research would be a missed opportunity to create an entirely different and optimistic future.

Optimism about AI requires us to invest in education and research, to promote a culture of innovation and critical thinking that encourages the exploration of new ideas and perspectives. Such an approach is crucial because AI has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of the world, offering new ways to solve complex problems and advance scientific discovery. For instance, in just one year, Deep Mind’s AlphaFold has dramatically expanded our knowledge of 3D protein structures from 1 million to over 200 million, approaching the expected total number of structures encoded by the human genome. We now have an enormous opportunity to explore new drug targets, and protein-specific therapies, as well as revolutionise research in synthetic biology (creating novel proteins). This underscores the tremendous potential of AI to accelerate scientific progress and drive positive change across a range of domains, especially the inequity of healthcare provided around the world,

At harrison.ai we understand that there are risks ahead – as is always the case with new & emerging technologies. On one hand there is the long-term risk posed by misaligned “general” AI (sometimes referred to as existential risk), and on the other hand there is the short-term risk posed by the economic, social and ethical implications of deploying even “narrow” AI models. When applying AI in medicine, the short-term risk is often front and centre of mind. That is why we believe in the following best practices:

- Safety: develop AI that is safe and secure, and that minimizes the risk of harm to people and the environment.

- Transparency: promote transparency in the development and deployment of AI systems and make information about how the systems work and their potential impact on society available to stakeholders.

- Fairness and non-discrimination: ensure that AI is developed and deployed in a way that is fair and does not discriminate against any populations, groups or individuals.

- Privacy and data protection: protect the privacy of individuals and ensure that personal data is handled in a responsible and transparent way.

- Societal and environmental impact: consider the broader societal and environmental impact of AI systems and ensuring that these systems are developed and deployed in a way that benefits society as a whole.

As AI continues to evolve and shape society, we must work towards developing AI systems that align with our mission to raise the standard of healthcare for millions of patients every day. We understand that while the risks associated with AI cannot be entirely eliminated, we must remain committed to our pursuit of knowledge and innovation, working tirelessly to minimize any potential for harm, and maximize the benefits of this powerful technology.

Article written by Jarrel Seah, Director of Clinical AI at harrison.ai & Simon Thomas, Clinical AI Associate at Franklin.ai.